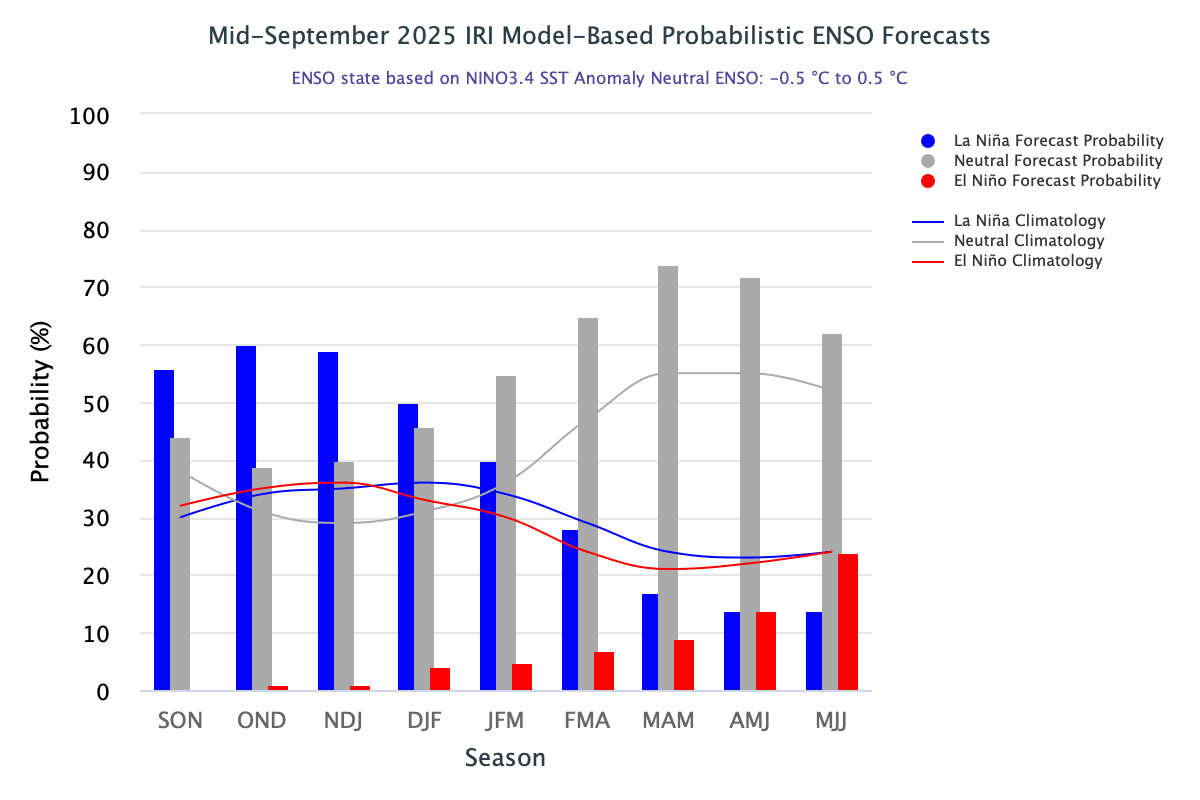

La Niña may return to impact weather and climate patterns from October onward, according to the WMO update. However, despite the temporary cooling influence of La Niña, temperatures are still expected to remain above average for much of the world. The probability of La Niña conditions is highest between November 2025 and January 2026. The chances are likely to exceed 60%, and La Niña will become the dominant category for December and January.

The La Niña event is expected to be brief and weak as well. The Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) during the event is projected to be similar to the last episode of 2024–25, when the index dropped to a lowest value of -0.6°C for the December–January–February quarter. Intrinsically, the period of peak winter for North India falls between 21 December and 31 January. This 40-day period is considered the harshest winter phase, known as ‘Chillai Kalan’ in Kashmir. The simultaneity of the La Niña peak and the typical grinding winter period may strike a harmonious note, unfolding bitter cold during the end of 2025 and the start of 2026. The ripple effect may send the winter chill as far south as Gujarat and Maharashtra, albeit for a shorter duration.

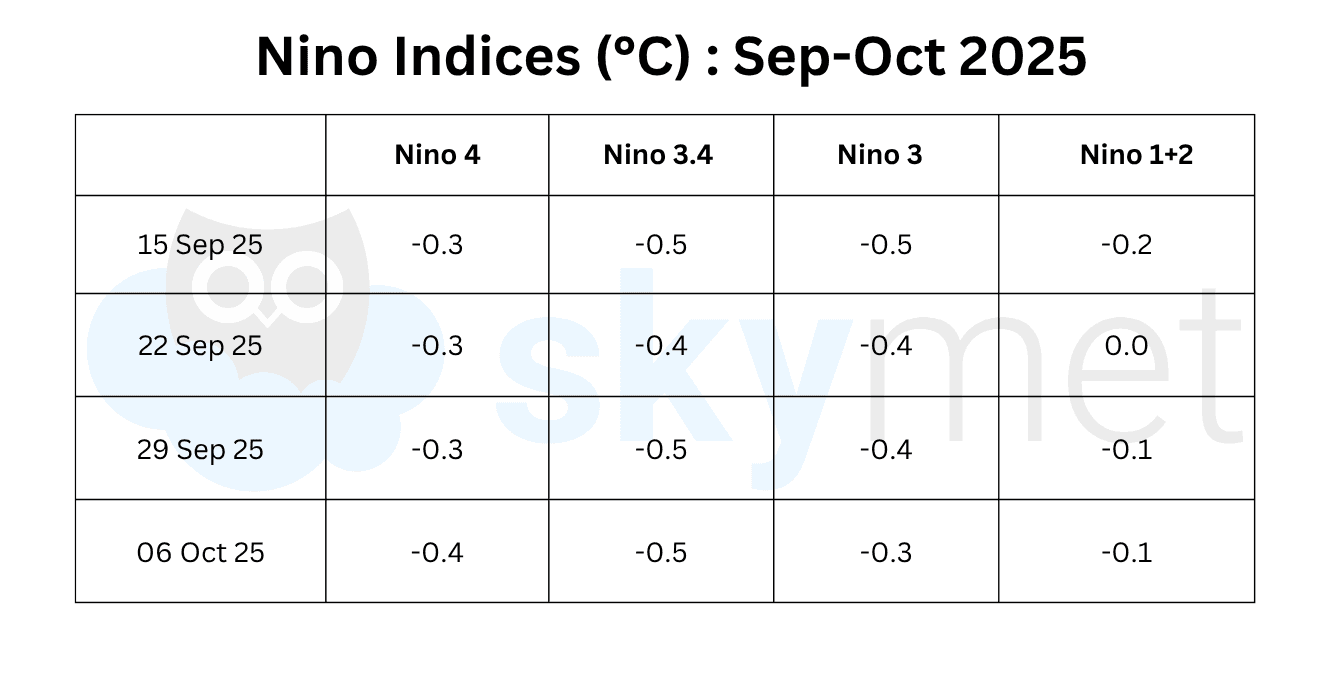

ENSO: La Niña and El Niño conditions are subsets of three key factors — sea surface temperature, subsurface water, and atmospheric conditions. Over the last few weeks, below-average subsurface temperatures have strengthened across the central and eastern Pacific. The surface temperature anomaly has also breached the threshold mark of -0.5°C three times in the last four weeks over the Niño 3.4 region. Both indicators suggest a rapid return of La Niña in the eastern equatorial Pacific. However, the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), the atmospheric wing of La Niña, is still holding a neutral stance. The average SOI for September 2025 was exactly zero. The SOI measures large-scale fluctuations in air pressure between the western and eastern tropical Pacific. This means the ocean surface and atmosphere are not yet resonating to establish a distinct La Niña event. A prolonged period of positive SOI values typically coincides with abnormally cold ocean waters across the eastern tropical Pacific, characteristic of La Niña episodes.

Since mid-August, equatorial SSTs have been near-to-below average in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. All Niño indices have maintained negative anomalies during this period. The Niño 3.4 index — the principal measure of ONI — has recorded a temperature anomaly of -0.5°C for the second successive week. The average value of Niño 3.4 for the past four weeks stands at -0.47°C, close to the threshold mark of -0.5°C. Sea surface temperature is generally slow to respond to both cooling and warming phases. Once subsurface temperatures sustain a drop through a layer of about 200 meters, the surface temperatures will follow. At this rate, the ONI for the September–October–November quarter is likely to reach or exceed the threshold mark of -0.5°C.

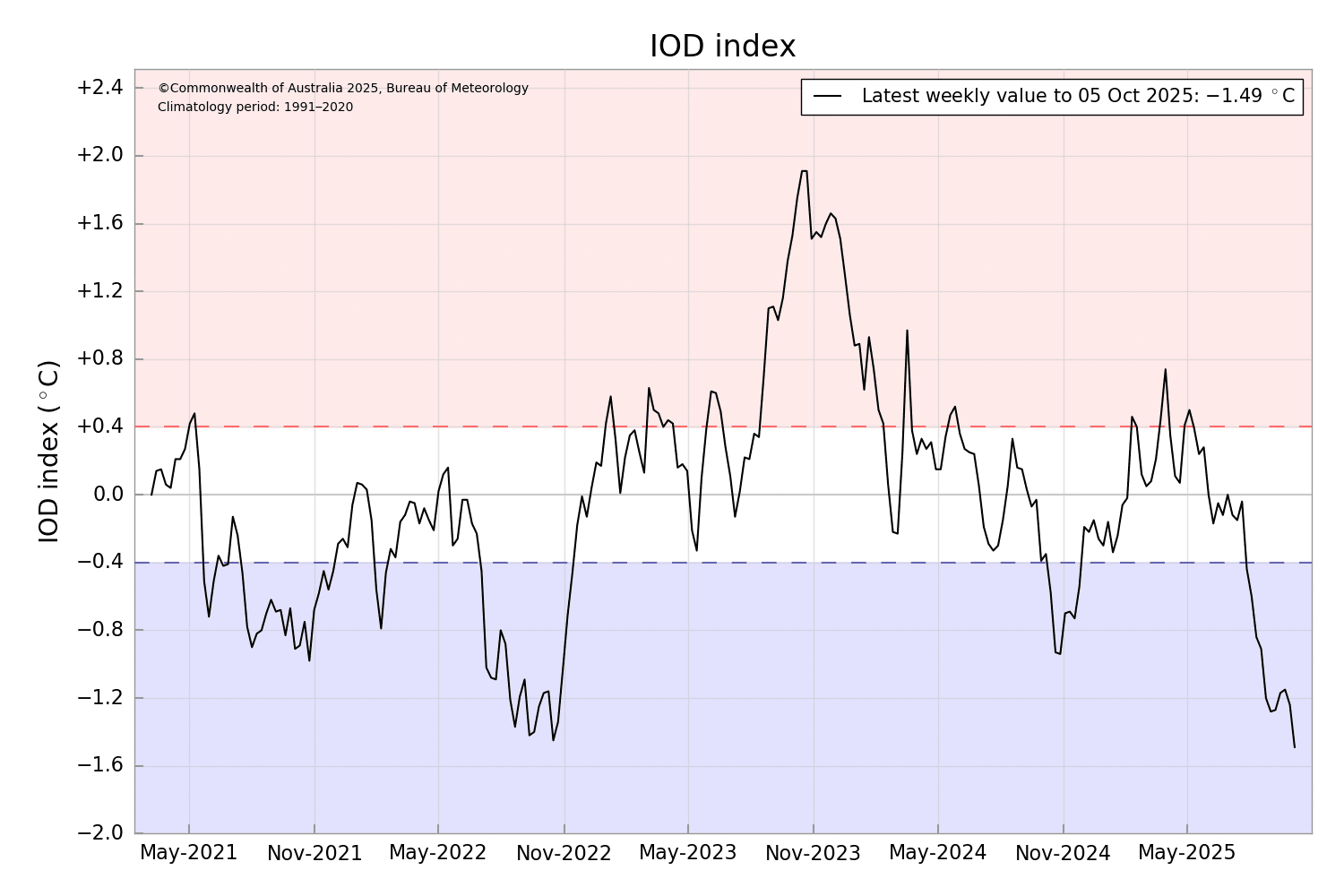

IOD: The negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is firmly established. The index has remained below the threshold mark of -0.4°C for the past 11 weeks. The latest IOD index value for the week ending 5 October 2025 was -1.49°C, the lowest in at least the last five years. The index value has stayed below -1°C for the seventh successive week, marking the longest and sharpest drop in recent history. The negative IOD event is expected to persist through the end of the year and return to neutral conditions by early winter 2026.

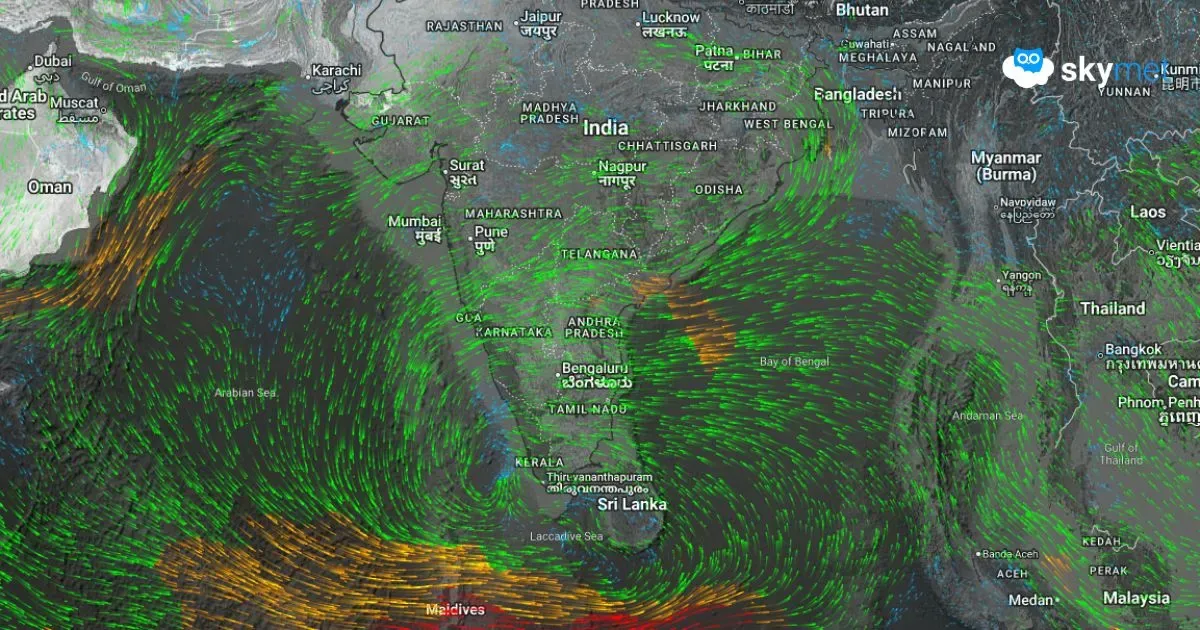

MJO: The Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) pulse remained weak and incoherent during September 2025. The signal meandered across phases but stayed confined within the unit circle since late August. A renewed eastward propagation of the MJO is likely, associated with an uptick in amplitude over the Indian Ocean. This positioning of the MJO will favor tropical cyclone development over the Northern Indian Ocean and Western Pacific during the next two weeks.

The La Niña event is generally correlated with colder and potentially harsher winters, particularly in northern India. Cooler Pacific waters tend to shift the westerly jet stream, influencing weather patterns and bringing lower temperatures to higher latitudes.